Tuesday, September 17, 2013

Why There's Just About No Inflation

Census released its broadest estimate of various income measures for 2012.The highlights:

Some graphs from the report:

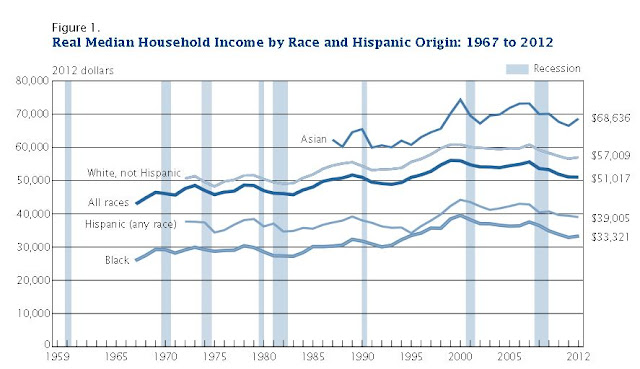

And of course real median incomes:

When interpreting these measures, it's important to remember that as new households form the median income should tend to shift downwards a bit. Also when looking at real median incomes by race, don't forget to factor in larger numbers of younger people among groups such as Hispanics and Blacks.

But regardless, income measures such as these do tend to accurately reflect the need for government welfare programs, although income from government welfare programs is not counted.

Now add to this the impact of this year's tax increases, and it's not hard to understand why we have low consumer inflation. We simply don't have the circulating money income to cover much in the way of cost increases.

We could, of course, take advantage of the Fed's optimistic largesse to simply borrow our asses off, but oh, wait, we already did that. We really can't do it again:

As a wild guess, more households still want to delever than otherwise. This chart shows nominal instead of "real" debt, but the dizzying rise in nominal debt since the 1990 real median household income point implies that we are still overloaded with debt. Those student loans aren't going to encourage the younger cohort to live large on a borrowed dime either.

The interesting thing is that there are two implications for the Fed. The first is that future guidance as to rates means little in terms of a houshold's propensity to borrow, except perhaps for home loans and auto loans (both of which are currently shifting to the less affordable). The second is that if they ever want to try to inflate out of this, they really need to do it pronto. Aging households imply that five and ten years down the line it will be impossible.

- Real median household income was 51,017 in 2012 vs. 51,100 in 2011. Not statistically significant.

- Since the income peak real median household income is down 8.3%. Since the peak before the previous recession (1999), real median household income has declined 9%.

- Real median household income is in fact very similar to the peak before the 1991 recession - just a tad under currently. More than two decades of declining real median household incomes spells "housing recovery", doesn't it? The future's so bright we have to wear rosy glasses. ...

- But actually some signs of recovery do exist. The bottom two quintiles either lost or held steady, and the top quintile and the top 5% lost. The middle two gained. These changes are not really statistically significant, but probably they really are, considering the looming tax increase pulled-forward income shift from 2013 to 2012, which showed up the most for the wealthiest households.

Some graphs from the report:

And of course real median incomes:

When interpreting these measures, it's important to remember that as new households form the median income should tend to shift downwards a bit. Also when looking at real median incomes by race, don't forget to factor in larger numbers of younger people among groups such as Hispanics and Blacks.

But regardless, income measures such as these do tend to accurately reflect the need for government welfare programs, although income from government welfare programs is not counted.

Now add to this the impact of this year's tax increases, and it's not hard to understand why we have low consumer inflation. We simply don't have the circulating money income to cover much in the way of cost increases.

We could, of course, take advantage of the Fed's optimistic largesse to simply borrow our asses off, but oh, wait, we already did that. We really can't do it again:

As a wild guess, more households still want to delever than otherwise. This chart shows nominal instead of "real" debt, but the dizzying rise in nominal debt since the 1990 real median household income point implies that we are still overloaded with debt. Those student loans aren't going to encourage the younger cohort to live large on a borrowed dime either.

The interesting thing is that there are two implications for the Fed. The first is that future guidance as to rates means little in terms of a houshold's propensity to borrow, except perhaps for home loans and auto loans (both of which are currently shifting to the less affordable). The second is that if they ever want to try to inflate out of this, they really need to do it pronto. Aging households imply that five and ten years down the line it will be impossible.

MaxedOutMama

MaxedOutMama